“From the ridge, Harlow looked like an octopus – the body boiled, drew its arms in, and then exploded, sending its arms darting in all directions.” – Jesse West, Madera County Sherriffs deputy and resident of Awahnee in 1961

On July 10, 1961, around 10:30 am, a young man with nothing but the best intentions took a book of matches, some kerosene soaked rags and he lit a fire in order to clear some brush. He had not been asked to start the fire, and he was in no way qualified to be attempting a burn of this nature. He struck that match because he had overheard two other employees of the Harlow ranch, located near Stumpfield Mountain in Mariposa county California, discussing the days work. They were going to be spending another hot day rounding up livestock, and if the hillside wasn’t clogged with brush, it would be a whole lot easier.

That young man could not have chosen a worse time to try to help. California had been in the grips of a multi-year drought, one of the worst in the states recorded history. Fire officials had been preparing for the resulting wildfire risk, and in advance of the 1961 fire season, they had readied 6,000 personnel, 60 air tankers and dozens of helicopters. Sadly, that would barely be enough to stop what would become known as the fastest moving fire in Californias history. It’s possible that this title has been overtaken in recent years, but this is not a record for which anyone cares to take the credit or assign a best-of medal.

The response to the Harlow fire was imediate and all encompassing. The Forest Service, California Department of Forestry (CDF) and inmate firefighers were engaged in battling the blaze by noon on the first day, but it was already beyond their control. The initial call was answered by CDF, and when they arrived they found that the fire had spread to approximately 2.5 acres. However, within minutes of their arrival it was completely out of control. A Forest Service meteorologist would later describe the resulting conflagration as “a full-scale, moving firestorm”.

Remnants of the store in Awahnee

Destroyed on the first day of the Harlow fire were the towns of Awahnee and Nipinnawasee, both of which were gone within an hour of the first building catching fire. Residents at first tried to defend their propertiers, but evacuations were ordered and the rate of spread was so fast that in most cases nothing could be done but to flee. Animals had to be left behind, and most residents escaped with only their most valuable posessions.

Tuesday, July 11, was the most intense and dangerous day of the event. The fire consumed 20,000 acres in just two hours. One man recounted that he was driving 50 mph on route 49 and he watched as the fire skipped across the tops of knolls and was traveling as fast as he was, if not faster. The evacuees from the fire zone were forced to drive into the town of Oakhurst to seek refuge from the flames. Eye witness accounts describe it as “bedlam”, and its a miracle that no one was injured or killed in a car accident.

On Wednesday, July 12, the whole of Deadwood mountain was consumed by flames in a matter of minutes. Eye witness accounts said that the flames moved so quickly up the mountain side that only the fronts of the trees burned. The back side remained green, which then allowed the fire to burn back down the side of the mountain.

By the third day, approximately 2,000 firefighters were on the lines, attacking the blaze with everything they had. Air tankers dropped 45,000 gallons of borate in 24 hours. A 40 mile perimeter was created with firebreaks, some the width of 3 bulldozer blades. According to a long time North Fork resident, Augie Capuchino, who was 8 years old at the time of the fire, “The Forest service went to the sawmill [in North Fork] to grab all the employees and put them on a bus with no training to go and fight the Harlow fire. My dad, my uncle and 3 brothers included”.

Drivers wait on Deadwood during the Harlow Fire

Also on the third day, officials ordered the evacuation of campgrounds on the south shore of Bass Lake. The town of North Fork, which lies just over the ridge from Oakhurst was also in danger as the fire was moving towards Thornberry mountain. At 12:30 pm, authorities closed California State Route 41 northbound of the town of Coarsegold to traffic.

On Thursday, July 13, Governor Jerry Brown declared the effected zone a disaster area. The fire was declared fully contained that afternoon. But the fire had other plans, as on Friday, July 14, it escaped containment in two seperate places, but the crews were able to join forces and subdue the spot fires by 6 pm. The Harlow fire was officially declared contained at 10 pm that evening.

The only human casualties of the Harlow fire were George and Etta May Kipp. On Tuesday evening, July 11, after already losing their home, the long time residents of Awahnee headed up Roundhouse Road in an attempt to find and warn their daughter who they feared was in imminent danger. They were warned multiple times to turn around, but in their desperate attempt to find their daughter they ignored all warnings and drove around the baricades. Tragically, their car was discovered by deputy Jesse West. The fire had overtaken their car, which ran off the road, killing George. Etta May, who was still alive when Deputy West arrived, had managed to get out of the car, but died enroute to the hospital. George was 78 and Etta May was 63.

The fire that started the morning of July 10 burned for 6 days. 41,200 acres of land were consumed in the blaze. 105 structures were lost to the flames, with an estimated $1.5 million in financial losses. When adjusted for inflation that amount is equal to $14 million today.

Sixteen days after the Harlow fire began, that young man who had lit the match admitted to starting the blaze, ending a manhunt that had looked at a variety of suspects but had finally lead to the young mans arrest. He was questioned for 8 hours, given a lie detector test, which he “flunked”, at which point he broke down and confessed. The following day, the sherriffs department took the boy on a tour of the disaster area, seemingly to impress on him the horrendous nature of the result of his act. During that tour, he showed the authorities exactly where he started the fire, which aligned with the official forensic determination of the fires origin by the authorities. He was arraigned and held over for a jury trial.

During the trial, his defense attorney argued that the youth had admitted to starting the fire under duress and was now repudiating the confession, denying throughout the trail that he had set the fire. A Modesto State Hospital director testified that the youth had an emotional age of 14-16, and was susceptible to influence due to a poor home life. Ultimately, the attempt to portray the young man as developmentally disabled was not the deciding factor in the outcome of the trial. After only 2 hours of deliberation, the jury unanimously acquitted the youth. They had objected to the wording “maliciously and willfully set the fire” and decided that he was incapable of understanding the consequences of his actions or of foreseeing the fires outcome.

The public, particularly those directly impacted by the fire, were outraged in the days and weeks after the Harlow fire. The CDF were the main focus of the publics ire. Bitter victims blamed their losses on what they deemed a poorly organized and mismanaged firefighting effort. Some of the complaints lodged at the agency were that fire equipment and personal had been seen sitting idle, homeowners had not been allowed to return to their property to attempt to battle the blaze, and that there was a lack of communication between the different agencies that had been fighting the fire. All of these points were countered by CDF officials, and eventually the threats of legal actions amounted to nothing.

In the years since the hard lessons of the Harlow fire, thepopulation of the area has increased dramatically. New construction replaced the buildings lost to the fire, and added more structures with each passing year. New subdivisions were built, and life moved on. However, the fear of another fire of this magnitude has continued to be prevalent in the community as well as the agencies tasked with protecting them.

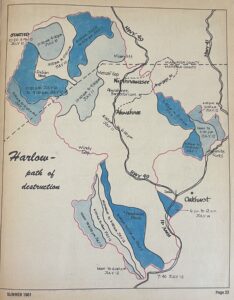

Map from Sierra Quarterly, Summer 1981, Harlow Fire Path Of Destruction

“The Potential for another conflagration similar to Harlow is much greater now,” admitted Darrell Wood of the California Department of Forestry. [quote taken from Sierra Quarterly, summer 1981]. “Where there were large trees and scattered timber before Harlow, there is now solid brush. Today, with more people and more structures, that same fire (Harlow) could take several hundred lives. Back then (1961), we had range lands on which to start backfires – now, with our subdivisions and increased population, there are many areas where we would have to forget fighting the fire itself in order to save structures,” said Wood. Still, 44 years after that statement, and 64 years after the Harlow fire itself, wild fire is still the number one fear in our mountain community.

In the wake of the Harlow fire, there was a large push by officials to educate and inform the public in regards to defensible peremeters, escape plans and general fire preparedness. Sierra News Online takes our role seriously, and in the coming weeks and months, as we ride out the peak fire season, we will be doing our best to bring you useful information on fire preparedness, updated info on current and recent fires in the area, and more.